In Malay-Muslim culture, one of the first encounters one would have with batik is part of funeral rites. The thin cloth typically in hues of golds, browns and blacks is often used as a modesty cloth of sorts while preparing the deceased for burial as well as to cover any mirrors in the house. While there is no basis for the use of batik in Islamic teachings, it’s a long-held Malay tradition that’s still being practised till today. And perhaps, one that has withstood more prevalently than wearing batik fashion.

“Initially, I started with no browns because I don’t particularly have positive memories of brown batiks. It has always been a death cloth to me,” says Oniatta Effendi, the passionate cultural entrepreneur behind Baju by Oniatta.

We sat across from each other in her cosy two-storey walk-up along North Bridge Road where Galeri Tokokita has been around since 2020. Fashioned as both a gallery space where talks (about batik of course) are held as well as a retail space for Baju by Oniatta, Galeri Tokokita is Effendi’s very own batik haven. The brand itself was launched in 2016 driven by her “obsession” with Indonesian batik.

Photo: Baju by Oniatta.

Batik’s roots aren’t exactly very clear cut. Archaeological samples of dye-resistance patterns have been traced to the Middle East and Egypt, dating back well before the 6th century. Records of the first known instances of Indonesian batik too varies, owing to the different types of batiks that are individual province to province. Java is often credited as the home of batik.

The essence of batik is in its wax-resist dyeing process where areas coloured with wax preserves the original colour of the fabric used. Artisans make use of natural materials such as silks and cottons as these tend to absorb the wax better.

The most handcrafted process of creating batik results in batik tulis (literally ‘written batik’) that involves the use of a canting (handheld copper container with a spout) for artisans to deftly trace and fill in designs on fabric with hot wax. Batik cap (‘cap’ means ‘stamp’) hastens the process of creating batik fabrics with the use of a copper stamp that’s already been moulded to the required design. This method is said to have been devised around the middle of the 19th century as the demand for batik grew. It is also not uncommon to see a combination of both batik cap and batik tulis together in one design.

For the most part, Effendi sticks to these two for Baju by Oniatta. “I like to give the wearer a sense of exclusivity; that they’re different and that one piece is meant for that one wearer. I also enjoy that process, however long, because of the intricacy of it,” she says when asked why only batik cap and batik tulis, instead of the quicker turnaround time afforded by machine-printed batiks. “That’s not batik!” she quips before admitting that she’s quite a purist in that sense.

Effendi—who used to wear many hats as a theatre practitioner and educator—has become quite the poster child for modern batik, especially in the Malay-Muslim community.

She takes the craft and its cultural nuances seriously. For Baju by Oniatta’s annual thematic collections typically launched during the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan, Effendi goes deep into research on colours and motifs that make sense as part of an overarching story. She checks in with the Indonesian artisans she works with to ascertain the meanings behind certain batik motifs and at times, gets input from friends who are batik researchers in Indonesia.

“They produce products as well and may be considered competitors. But the beauty of the batik community is that we’re generous with what we want to share, because I think it benefits a larger community,” Effendi explains.

irreverent batik

On the other side of the batik coin, there’s Desleen Yeo, founder of YeoMama Batik. Her bubbly persona comes through in the brand’s social media posts—a constant collaboration with her Indonesian-born mother—and is reflected in her madcap designs.

Photo: YeoMama Batik.

Yeo’s approach to batik is irreverent and guided by her own style preferences, much like her design process. “The two motifs that I have particularly stayed away from are the ones with the wayang (Indonesian shadow puppets) and chickens. But it’s not because of any cultural meanings, just personal preference. I feel, as a business owner, my customers would also probably feel the same way and wouldn’t want to wear them either,” Yeo says.

Growing up, Yeo was surrounded by batik by way of the Indonesian side of her family. But it was never something that she felt very strongly for. “The batik my mother bought for me were not the designs I’d want to wear,” she tells me offhandedly.

Yeo, who has been in the business for five years, now appreciates how batik artisans work—their patience and niche skill set. It’s inspired her to want to help preserve what has always been part of her culture through using batik as a creative medium beyond its traditional notions.

In fact, Yeo got married in a number of batik outfits including a porcelain blue wedding gown made from batik featuring a kawung (a four-petalled floral motif shaped like a palm fruit) and enhanced with an embellished neckline. Yeo’s favourite is a batik jumpsuit. She pulls out the detachable shoulder piece that she keeps in a cupboard as an example to show prospective clients the kind of embellishments that can be done for customised pieces. It’s stunning—three-dimensional embroidery work that’s skilfully done on an already heavily patterned fabric.

According to Yeo, the typical YeoMama Batik customer isn’t necessarily a batik lover. “I feel like they don’t really care whether or not it’s handmade. ‘I just like the print; it’s so colourful.’ And the cuts are suitable for them so I feel like that’s the main draw,” she explains. The education on the handcrafted processes comes naturally, pointing out typical batik flaws such as minor misalignments of colours and marks left by wax residues.

As she tells me, her mother is often mistaken for being Peranakan, which is understandable. In Singapore, a Chinese-looking lady fronting a batik label practically screams Peranakan. The reality is that batik is intercultural. It may be known by different names, but the process is similar, if not the same.

Looking at OliveAnkara’s boldly coloured prints, there’s no denying that founder, designer, and creative director Ifeoma Ubby’s brand is steeped in African culture. Nonetheless, it is easy to see similarities between ankara—also known as African wax prints, and one of the most common textiles characterised by bold colours and designs—and batik when you look closely.

paying homage

“In the ankara process, when they create the fabric, they use double the amount of wax and print on both sides. There’s technically no back nor front to the ankara,” explains Ubby. In her opinion, the fabrics are stiffer and more colourful than batik cloth. The patterns and motifs are also different, although they share some similarities.

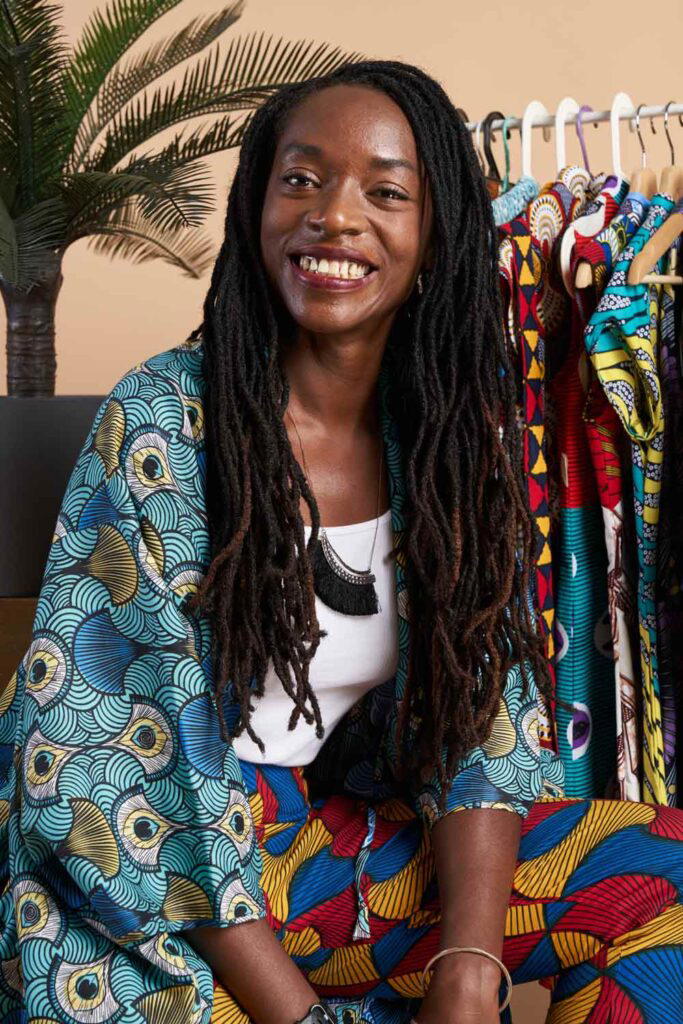

Photo: OliveAnkara.

Ubby herself is a product of many cultures. Even though she was born and raised in Italy, Ubby was still surrounded by her Nigerian culture. “Luckily enough, where I used to be, there were a lot of African communities and a lot of Nigerians at any event,” she expresses. It was her move to Singapore almost a decade ago that prompted her to want to celebrate her Nigerian culture even more, owing to the fact that it’s one that’s not well-represented here.

OliveAnkara was launched in 2017 and continues to champion African culture with the Ankara fabrics reinterpreted into modern fashion. Ubby tells me that she does have first-time customers mistaking the Ankara for batik but they’re more so drawn by the vibrant colours and prints than anything else. The confusion then leads her to share a fair bit about her culture.

“When I decided to start OliveAnkara, I had to ask my family whether it was good because I knew that I was preparing for a different kind of customer—Asians and Caucasians. They all gave me a thumbs up for doing that. I need to think about it as a way of enhancing and promoting my culture,” she explains when asked if she had any qualms modernising such an integral part of African culture.

It’s a prevailing issue brought about by a more culturally sensitive society. Modernising a fabric that has such a profound presence in cultures all over the world is not an easy task, especially since it is not uncommon for communities to claim ownership of even something as nuanced as batik.

a question of culture

“We are bound to fall into certain traps, whether knowingly or unknowingly. Ultimately, I think your intentions are incredibly important—why you’re doing what you’re doing. But it takes time to reflect,” Effendi tells me as she recalls an incident when individuals on social media erroneously thought she was claiming batik as Singaporean. “I never shy away from the fact that Baju by Oniatta’s batiks are from Indonesia because it’s all about giving life and support to the ecosystem and being part of it.”

Yeo and Ubby concur. The term cultural appropriation is frequently bandied about, but for these entrepreneurs, it’s the intention that distinguishes appropriation from appreciation. For Yeo it’s reiterated through explaining the different motifs used in her collections. Ubby takes it up a few notches by incorporating other cultural elements that’s part of Singapore’s melting pot. Ankara fabrics have been turned into Chinese New Year-appropriate cheongsams as well as modest fashion perfect for Hari Raya celebrations—all done as love notes to a city that she now calls home.

Even without these more out-of-the-ordinary touches and interpretations of batik, the very existence of these Singapore-based brands help tell the stories of time-honoured craftsmanship. What’s modern nowadays? Appreciating, celebrating, and most importantly, sharing the beauty of one’s culture—and the batik is one.